Is the epidemic accelerating or coming under control in China?

At this time, it’s hard to know what the true state of the COVID-19 epidemic is. There are grounds for both optimism and pessimism.

The raw data shows the number of confirmed cases increasing day-by day. However, the number of confirmed cases is just the tip of the iceberg. Some people, particularly younger people, only show mild symptoms from COVID-19 infections and may not be aware that they are carrying and passing on the disease.

What does the data show?

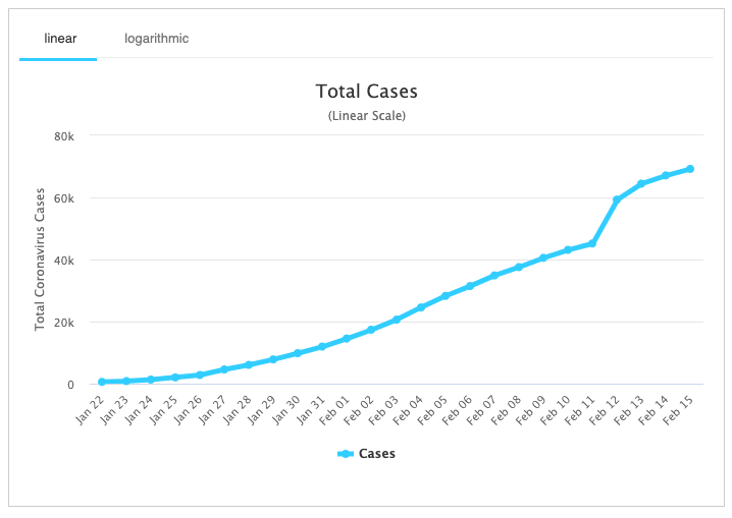

However, amongst the “fog of war” there is also a glimmer of optimism. The official tally of confirmed COVID-19 cases is shown below in graphs from the Worldometers website.

The first graph, plotted on a linear scale, shows a fairly steady rise in the number of COVID-19 cases. This appears alarming at first sight, especially with the big step up on February 12. That was due to a change in how cases were confirmed in China. I understand that such changes are not particularly unusual in the midst of a novel disease outbreak, but they also reduce confidence in the data.

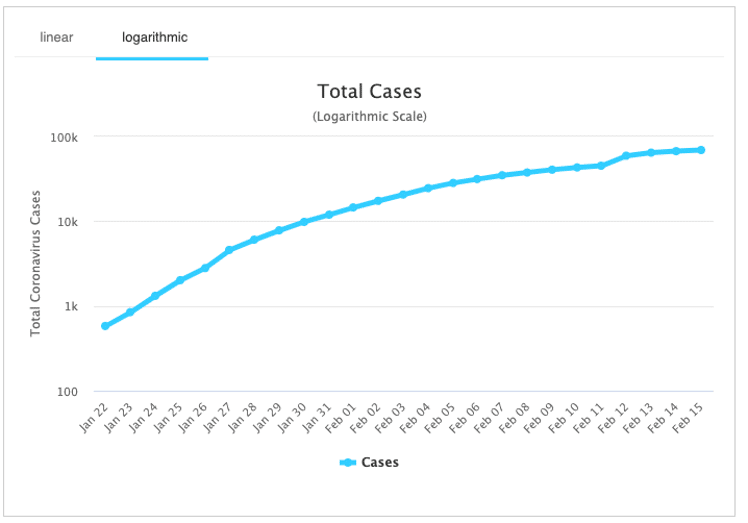

The second graph below is plotted on a logarithmic scale. This shows the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases is rising proportionately by less and less each day. The number of deaths follows a similar pattern. Is this evidence of a disease that gradually coming under control. Alternatively is it evidence of a health system which has simply reached capacity? At this stage we don’t know.

Meanwhile epidemic modelling based on the number of cases identified overseas indicates that:

- the virus was circulating and spreading in Wuhan for a month or more before the first case was detected

- only around 10% of cases are currently being officially diagnosed and reported

A large body of undiagnosed cases should not be surprising given that the symptoms in younger people tend to be mild. This characteristic, together with the relatively high transmissibility makes the disease hard to control.

What does it mean?

Some say that there’s a high likelihood that COVID-19 will become self-sustaining in other countries. The disease has already spread to 28 other countries and territories as of 15 Feb 2020. This has mainly been through people with direct contact with China although some person-to-person transmission has also occurred outside China. One case has been reported in Africa. Meanwhile the World Health Organisation has declared this as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

Fortunately, most offshore cases of COVID-19 infections to date have been in relatively wealthy countries who can afford good health care systems. If the disease becomes prevalent in parts of the world which aren’t so well off, then we’re probably looking at it becoming another virus that adds to the global health burden of seasonal flu. That burden is already high. In the US alone the seasonal flu is estimated to result in an estimated 140,000 – 800,000 hospitalisations and 12,000-60,000 deaths annually.

Serious cases of seasonal flu tend to afflict those who are elderly or otherwise infirm.

International Expert Opinion

While China is working very hard to contain COVID-19 and is showing some signs of success, some international experts are pessimistic about the outlook:

This virus is probably with us beyond this season, beyond this year, and I think eventually the virus will find a foothold and we will get community-based transmission.

Dr. Robert Redfield, Director, CDC, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

I think we should be prepared for the equivalent of a very, very bad flu season, or maybe the worst-ever flu season in modern times …

Prof. Marc Lipsitch, Prof. of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health.

COVID-19 Death Rate

How bad is COVID-19? Unlike the seasonal flu, there are no vaccines or treatments and, crucially, no pre-existing immunity in the population.

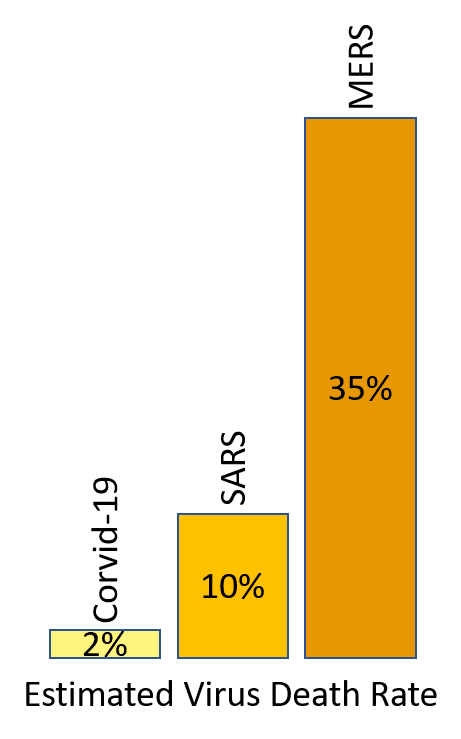

The World Health Organisation has suggested that the death rate from COVID-19 may be around 2%. That’s less than SARS (10%) or MERS (37%) but is still a major concern.

The World Health Organisation has suggested that the death rate from COVID-19 may be around 2%. That’s less than SARS (10%) or MERS (37%) but is still a major concern.

It is difficult to know how deadly a disease is in the middle of an outbreak as only the most severe cases may present to hospitals. This can lead to an apparent case fatality rate which is higher than the real rate. A simple way of estimating the case fatality rate is only to consider cases where the outcome is known (being death or recovery). The simple estimator is the number of deaths divided by the total number of patients who have died and recovered.

Health systems outside of Hubei province are under less strain and may provide a better indicator of case fatality rates under more normal conditions. Looking only at data from all other provinces in China and internationally, the completed case counts as of 16 February are 73 deaths and 4001 recovered (1.8 %). This is close to the WHO estimate of 2%. There are still uncertainties. If there are many other cases with mild symptoms which are undiagnosed in these centres, as epidemic modelling suggests, then the actual case fatality rate may be significantly lower.

Analysis of early cases from Wuhan indicate that the disease was initially most prevalent in older people and men in particular. The evidence from early cases is that the disease is more likely to lead to complications in older people or those with existing conditions. Early data showed more fatalities amongst men but whether men are more prone to complications and dying as a result of the disease remains an open question.

COVID-19 Vaccines

Various organisations are racing to prepare vaccines, but it typically takes a long time to identify, trial, test and then manufacture vaccines in volume. History indicates that countries where manufacturing facilities are located can be reluctant to release vaccines until they have enough to cover their own populations. Critical sectors such as health care professionals will be allocated top priority everywhere.

Various organisations are racing to prepare vaccines, but it typically takes a long time to identify, trial, test and then manufacture vaccines in volume. History indicates that countries where manufacturing facilities are located can be reluctant to release vaccines until they have enough to cover their own populations. Critical sectors such as health care professionals will be allocated top priority everywhere.

While advances in technology are accelerating the development of vaccines, we should not expect a vaccine to be generally available in New Zealand before the end of 2020. Likewise, some existing drugs show treatment promise, but they may not be generally available until it’s too late.

If this does become a self-sustaining global pandemic then I expect that it would have become an epidemic in NZ well before then. For those of us who are not in the healthcare profession that suggests that we should not plan to rely on new vaccines or treatments, in 2020 at least.

In accompanying posts I comment on what we at Navigatus are doing to prepare in case the epidemic takes hold in New Zealand and Geraint Bermingham recounts the lessons from his experience on the frontline of responding to the SARS epidemic in an international airline.

About the Author – Kevin Oldham

Kevin Oldham is a director of Navigatus with a depth of experience in helping clients to achieve success in an uncertain context. A brief profile for Kevin can be found here.

Comments (2)

[…] explore whether or not COVID-19 may become a global pandemic in an accompanying post. Whether that happens is beyond our individual control. But there are things that we can do to […]

[…] now have COVID-19 (please see Kevin Oldham’s excellent personal perspectives in earlier posts), we’ve had SARS II, Swine flue, Middle Eastern flu, Ebola – the list goes on – […]